By: Alyssa Loskill

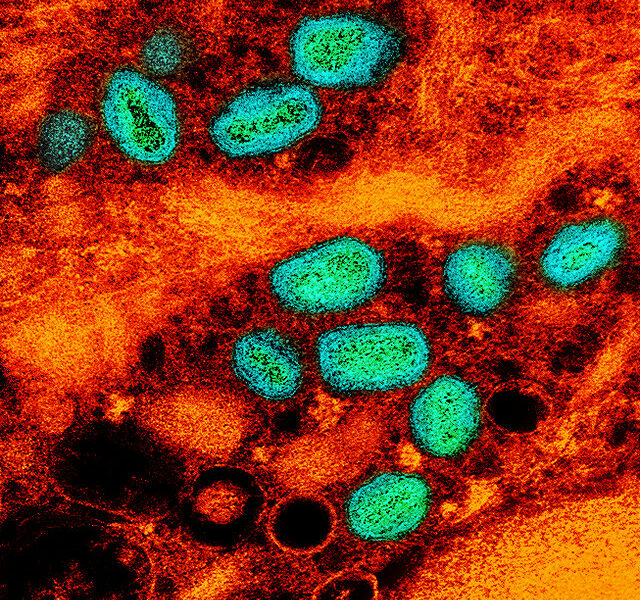

Image courtesy of Brian Ralphs via Flickr Creative Commons

BACKGROUND

When Americans think about anthrax, we think about the weaponization of white powder that was sent to U.S. Senators and news agencies after the September 11th terrorist attacks [1]. This was the first time Americans came face to face with the airborne pathogen as it wreaked havoc across the United States. However, in southern African wildlife areas, anthrax is a common, naturally occurring bacteria spore present in the soil. The spores can survive for many decades in the soil and during drought-stricken periods, when there is minimal water at watering holes, animals tend to disturb sediment while drinking and end up ingesting anthrax spores [2]. Due to the potential rapid onset of disease, a veterinary faculty member at the University of Pretoria notes that because animals with anthrax tend to die close to water sources, their remains are washed into the water and build up in the silt [3]. This perpetuates the cycle of infection and can increase transmission to wildlife including elephants and plains ungulates.

IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Historically, human anthrax cases in Zimbabwe peak in November before the first rains and during the worst drought conditions [4]. The current drought in Zimbabwe, which has been named the worst in its history, paired with the 18-month drought in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, has only exacerbated the issue [5]. According to Reuters, the government of Gaborone, Botswana, and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks state that over 100 elephants have died in the past two months. The most recent reported deaths, 14 in one week (October 22), occurred in northern Botswana along the Chobe River front and Nantanga areas, supporting the understanding that many of the infected animals die close to watering points [6].

PUBLIC HEALTH RELEVANCE

From a public health perspective, anthrax is not contagious from person to person, although people can get infected if they are working with, disposing of, or eating infected animals or animal products. Despite widespread annual vaccination of cattle and goats, they are still at risk of contracting anthrax if they drink from the same water sources where infected animals drink or have died. Anthrax infections in cattle are highly correlated with human infections via interaction with infected carcasses during skinning and processing hides and handling meat [4]. Additionally, observational studies have shown that meat from dead animals that are potentially infected with anthrax are sometimes consumed by communities or processed for goods, putting people at risk of contracting the infection. In response, park personnel in affected areas have been working quickly to correctly dispose of the elephant carcasses by burning them to reduce the potential of animal scavenging or any human interaction [6]. The anthrax vaccine is rarely administered to humans because it has not been sufficiently tested. If treated early, anthrax can be cured with antibiotics or antitoxins but if left untreated, it can be fatal [7].

IS THIS HELPING OVERPOPULATION?

It is also important to note that countries in this region are struggling with elephant overpopulation. The drought conditions have led elephants to raid human settlements for food, destroying over 17,000 acres of crops and threatening communities. Several southern African countries have begun exporting elephants to China and Dubai and even relaxing the global ban on the ivory trade to encourage culling [4]. At this time, the anthrax-related deaths in these elephant populations could be helping to naturally regulate the overpopulation issue. Although, continued vigilance disposing of the carcasses is necessary to minimize the transmission potential to livestock and humans.

Sources:

[1]: https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/resources/history/index.html

[2]: https://cdc.gov/anthrax/basics/index.html

[3]: https://epicore.org/#/events_public/articles/1261

[4]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3467405/

[5]: https://phys.org/news/2019-10-dozens-elephants-die-zimbabwe-drought.html).

[7]: https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/medical-care/treatment.html