Image courtesy of Sokwanele – Zimbabwe via Flickr Creative Commons

The Current Situation

On September 8, 2019, a cholera outbreak was declared in four localities in the Blue Nile State in south-eastern Sudan by the Sudan Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH). The first detected case in this outbreak occurred on August 28, 2019. As of October 12, 2019, cholera had spread to the adjacent Sennar State as well and a total of 278 suspected cases had been identified with 8 reported deaths (1-2).

Sudan has been plagued with cholera in the past, with the most recent outbreak lasting from June 2016 to February 2018. The 2016-2018 outbreak has been the longest and largest outbreak of Cholera to date in Sudan, with over 20,000 suspected cases and 436 reported deaths total (3). Due to Sudan’s over-burdened health infrastructure, limited access to clean water outside of its capital of Khartoum, widespread poverty, food insecurity, and recent severe rainstorms and flooding, the World Health Organization (WHO) is fearful that the current outbreak may grow rapidly if not dealt with swiftly. The areas at highest risk for spread of infection are located downstream the river Nile from the Blue Nile and Sennar States, as this is the main source of drinking water, as well as a common area for cleaning and/or defecation for many Sudanese, including those living in Khartoum (1,2).

Cholera: Defined

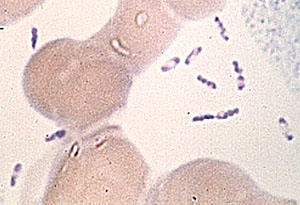

Cholera is a virulent bacterial disease that is obtained through drinking contaminated water. Infection occurs when a person ingests water contaminated with the fecal matter of another infected person. As an outbreak grows, especially in places where there is poor sanitation and inadequate water treatment, it can become very difficult to stop the spread of infection (2,4).

When an individual becomes infected with cholera, they have a 10% chance to exhibit severe symptoms, which include profuse diarrhea, vomiting, and leg cramps. In these individuals, dehydration, shock, and death can occur very quickly if access to clean drinking water is not available (4). Luckily, treatment for infection can be quite simple. Often, individuals are given Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS), which is a readily made mixture of sugar, salt, and water that helps to swiftly alleviate the effects of dehydration (4). Another strategy for combating the spread of cholera is the use of Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV), which can be easily disseminated and taken without medical observation. Under normal circumstances, the vaccine must be taken in two doses, at least two weeks apart; however during an outbreak, one dose of OCV has been shown effective (5).

Public Health Response

Due to the Sudanese FMoH swift recognition and declaration of this cholera outbreak, WHO has been able to rapidly respond and mobilize an outbreak containment response in the affected areas. In addition to disseminating a standardized case definition to healthcare providers to increase surveillance, the FMoH has activated 14 Cholera Treatment Centers across the Blue Nile and Sennar States (1). With the help of international partners, WHO has been able to stock these treatment centers with enough cholera treatment kits containing ORSs to treat over 500 individuals. Furthermore, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) has launched an OCV campaign to target 1.6 million people in these states, with many of the OCV doses coming from the WHO global stockpile (1).

Aside from directly treating individuals, WHO has been working with the ministries of health of the individual states to increase water quality surveillance and testing efforts. Alongside this effort, water chlorination efforts, which can kill the cholera bacterium, and health promotion education on infection prevention, have greatly increased in the affected areas (1).

References

- https://www.who.int/csr/don/15-october-2019-cholera-republic-of-the-sudan/en/

- https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-09-cholera-outbreak-dead-sudan.html

- https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-declares-end-its-longest-cholera-outbreak

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/general/index.html

- https://www.stopcholera.org/sites/cholera/files/oral_cholera_vaccine_what_you_need_to_know.pdf