Nigeria remains in the midst of a meningococcal meningitis outbreak that began this past December. Thirty-eight Local Government Areas, within the six states of Zamfara, Sokoto, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, and Yobe, have reached epidemic threshold status. The case counts are now estimated to be 8,057 suspected cases, with 230 (2.9%) confirmed cases [1], and 813 deaths (10%) [2]. The most affected age group in the epidemic is 5 to 14 year olds, who make up about half of the total reported cases [8].

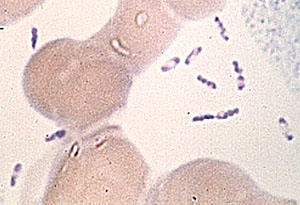

Meningococcal meningitis infection is caused by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis. About one in ten people harbor the bacteria in their nose and throat without experiencing any symptoms of the disease. However, the bacteria can invade other parts of the body and cause severe illness. The bacteria primarily spread from person-to-person by contact with respiratory and throat secretions, such as saliva or sputum. Infection occurs from extended exposure to, or close contact with, the bacteria. Common symptoms include sudden fever, headache, and stiff neck [3]. If untreated, meningococcal meningitis is fatal in approximately 50% of cases [4], and is fatal in up to 10% to 15% of cases treated with antibiotic therapy [5].

There are five different types or strains of Neisseria meningitidis (A, B, C, W, and Y) that cause the most disease worldwide [6]. In the current outbreak, 157 of the 230 (68%) confirmed cases were found to be serotype C infection. Interestingly, no Local cases of Neisseria meningitidis C have been reported within Yobe State, despite seeing other serotypes reported.

Many regions of Nigeria fall into what is known as the “meningitis belt”, a portion of sub-Saharan Africa that experiences the highest rates of meningitis in the world. Disease outbreaks are most common during the dry season, which spans from December through June. Serotype C first emerged in Nigeria in 2013, and has continued to be pervasive in the country since. Following its emergence, outbreaks have occurred from Neisseria meningitidis C in both 2014 and 2015. Both outbreaks resulted in more widely distributed cases than those seen in the original 2013 serotype C outbreak [8]. The prevalence of serotype C infections has been growing; while meningitis outbreaks in the belt have occurred for over a century [9], prior outbreaks in Nigeria mainly involved serotype A, of which a vaccine is available and widely distributed [7]. However, the emergence of serotype C has added an additional threat and significantly increased the number of reported meningitis cases in recent years.

As a result of the current outbreak, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control is receiving support from the WHO, United States’ CDC, and UNICEF via intensified surveillance, capacity-building for case management, and risk communication activities. A mass vaccination campaign is also underway, with over one million vaccines donated to Nigeria from various health organizations around the world [4]. While these efforts may end the current outbreak, there remains significant work to be done to create a long-lasting or sustainable solution, reducing the incidence and impact of meningococcal meningitis in Nigeria over time.

Sources:

[1] http://outbreaknewstoday.com/nigeria-meningitis-case-count-tops-8000/

[2] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-disease-idUSKBN17S25P

[3] https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/meningococcal-disease

[4] http://www.who.int/emergencies/nigeria/meningitis-c/en/

[5] https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/mening.html

[6] https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/about/causes-transmission.html

[7] [3] http://www.who.int/emergencies/nigeria/meningitis-c/en/

[7] http://www.who.int/csr/don/24-march-2017-meningococcal-disease-nigeria/en/

[9] Greenwood, B. (2006). 100 years of epidemic meningitis in West Africa- has anything changed? Tropical Medicine and International Health, 11(6), 773–780.