Researchers have mapped the genome of the Tasmanian devil and the fatal tumorous cancer that threatens to decimate the already endangered species. Since the disease was first recorded in 1996, up to 90 percent of the devil population has been destroyed by devil facial tumor disease (DFTD).

Elizabeth Murchison at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute has dedicated her career to the devil’s plight and recently contributed to a breakthrough research study published in the journal Cell that may provide some insight into the control of the fatal cancer.

The research team led by Murchison attempted to reconstruct the DNA of the original devil by sequencing the genomes of two healthy devils and the genomes of several cancerous tumors from opposite ends of Tasmania. Analysis of the results revealed important information regarding the original devil’s genetic makeup and the mutations that arose as DFTD developed and progressed.

A similar study published in Public Library of Science (PLoS) compared the genome sequence of a non-cancerous devil to those suffering from DFTD. Janine Deakin from the Australian National University directed the team that discovered that, in infected samples, tumors evolve very slowly and key chromosomes are completely jumbled.

Through investigative genotyping, the researchers were able to identify the original devil that first carried the cancerous mutations. Every case of DFTD can be traced back to this single “immortal” devil, a female who died more than 15 years ago. Although most cancers are restricted to the survival of the host, DFTD has survived by acquiring certain adaptations that permit transmission between hosts.

The discoveries made by the two teams may have profound effects on both Tasmanian devil populations and human populations. Further research on tumor causing mutations might identify specific genes that could be targeted for therapeutic interventions. Additionally, a better understanding of the cancer’s ability to avoid detection by the immune system might provide the information necessary to promote vaccine development.

Furthermore, since the devil tumor progresses at a very slow rate, it can be used as a model to determine how human cancers develop and change. The tumor’s stable genome also suggests that cancer cells do not need to express numerous mutations to be transmissible. Although transmissible cancers are very rare, an increased understanding of DFTD may be useful to prepare for the unlikely event of a human-to-human contagious cancer.

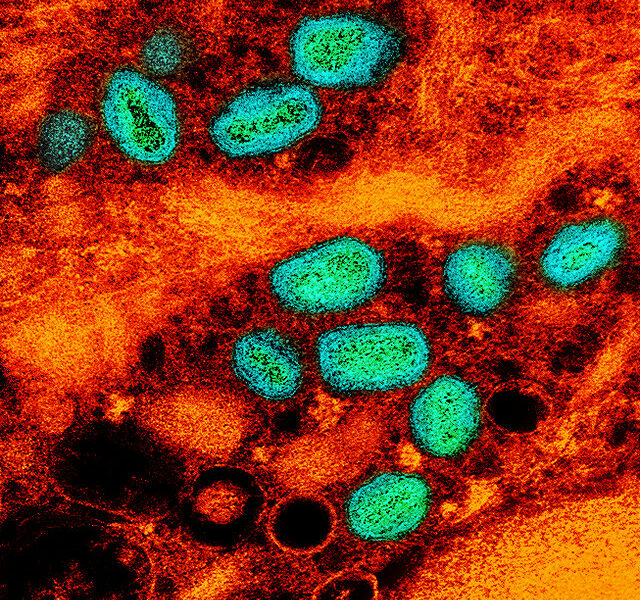

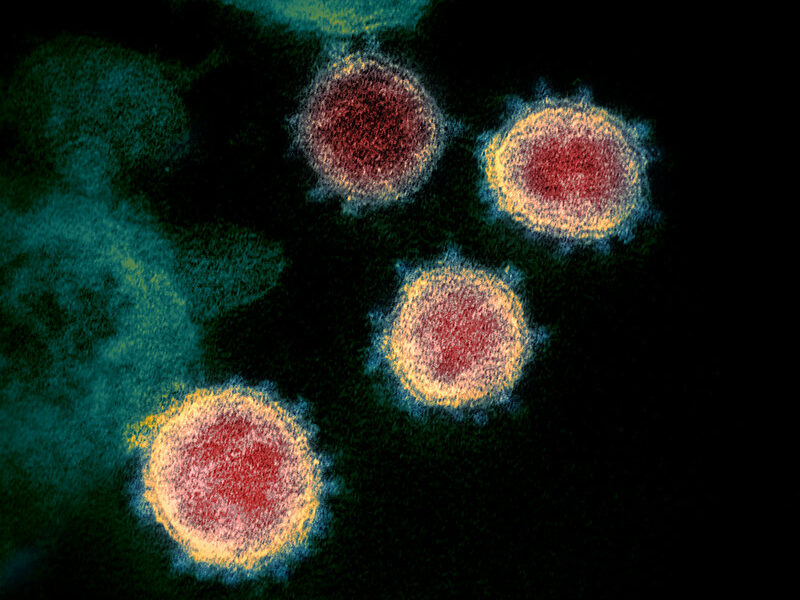

DFTD is one of only two naturally occurring transmissible cancers. The other is canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT), which is spread between dogs during copulation. DFTD, on the other hand, is spread by the direct transfer of living cancer cells through bites, usually during mating or feeding interactions. Animals infected with DFTD develop tumors on the face and inside the mouth, which often spread to other parts of the body where secondary tumors form. Death follows within a few months, often from starvation, as the tumors make it difficult to eat.

Over the last two decades the wild Tasmanian devil population has declined drastically. They are exclusively found on the Australian island of Tasmania, where only a small colony of completely disease-free devils exists in the northeast part of the island. Some areas are so impacted by DFTD that more than half of the devil population is infected and will likely die as they reach reproductive maturity.

Both the Australian government and the International Union for Conservation of Nature placed the devil on the endangered species list. In 2005, the Australian government supported the Save the Tasmanian Devil Program that captured 270 healthy devils, to be re-introduced into the wild once the disease is eliminated.

If the cancer cannot be properly managed and conservation strategies are not appropriately employed, the Tasmanian devil faces extinction within the next 25 to 30 years. Murchison and Deakin’s conclusions provide the necessary push to foster innovative research methods that may ultimately save the devil.